reader comments

136 with 102 posters participating

When we use browsers to make medical appointments, share tax returns with accountants, or access corporate intranets, we usually trust that the pages we access will remain private. DataSpii, a newly documented privacy issue in which millions of people’s browsing histories have been collected and exposed, shows just how much about us is revealed when that assumption is turned on its head.

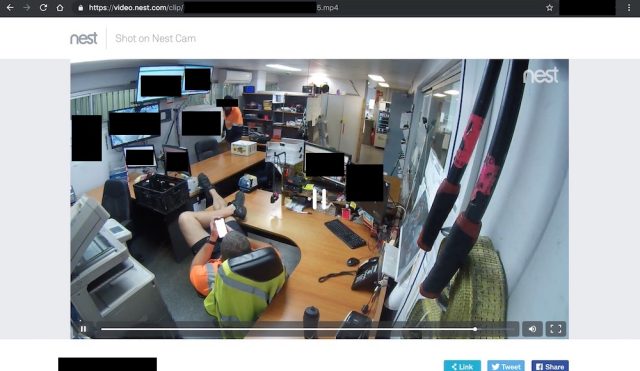

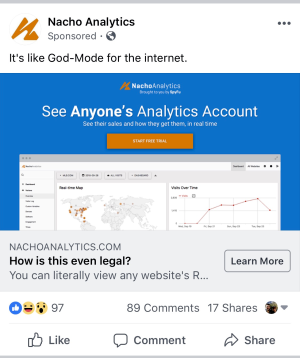

DataSpii begins with browser extensions—available mostly for Chrome but in more limited cases for Firefox as well—that, by Google’s account, had as many as 4.1 million users. These extensions collected the URLs, webpage titles, and in some cases the embedded hyperlinks of every page that the browser user visited. Most of these collected Web histories were then published by a fee-based service called Nacho Analytics, which markets itself as “God mode for the Internet” and uses the tag line “See Anyone’s Analytics Account.”

Web histories may not sound especially sensitive, but a subset of the published links led to pages that are not protected by passwords—but only by a hard-to-guess sequence of characters (called tokens) included in the URL. Thus, the published links could allow viewers to access the content at these pages. (Security practitioners have long discouraged the publishing of sensitive information on pages that aren’t password protected, but the practice remains widespread.)

According to the researcher who discovered and extensively documented the problem, this non-stop flow of sensitive data over the past seven months has resulted in the publication of links to:

- Home and business surveillance videos hosted on Nest and other security services

- Tax returns, billing invoices, business documents, and presentation slides posted to, or hosted on, Microsoft OneDrive, Intuit.com, and other online services

- Vehicle identification numbers of recently bought automobiles, along with the names and addresses of the buyers

- Patient names, the doctors they visited, and other details listed by DrChrono, a patient care cloud platform that contracts with medical services

- Travel itineraries hosted on Priceline, Booking.com, and airline websites

- Facebook Messenger attachments and Facebook photos, even when the photos were set to be private.

In other cases, the published URLs wouldn’t open a page unless the person following them supplied an account password or had access to the private network that hosted the content. But even in these cases, the combination of the full URL and the corresponding page name sometimes divulged sensitive internal information. DataSpii is known to have affected 50 companies, but that number was limited only by the time and money required to find more. Examples include:

- URLs referencing teslamotors.com subdomains that aren’t reachable by the outside Internet. When combined with corresponding page titles, these URLs showed employees troubleshooting a “pump motorstall fault,” a “Raven front Drivetrain vibration,” and other problems. Sometimes, the URLs or page titles included vehicle identification numbers of specific cars that were experiencing issues—or they discussed Tesla products or features that had not yet been made public. (See image below)

- Internal URLs for pharmaceutical companies Amgen, Merck, Pfizer, and Roche; health providers AthenaHealth and Epic Systems; and security companies FireEye, Symantec, Palo Alto Networks, and Trend Micro. Like the internal URLs for Tesla, these links routinely revealed internal development or product details. A page title captured from an Apple subdomain read: “Issue where [REDACTED] and [REDACTED] field are getting updated in response of story and collection update APIs by [REDACTED]”

- URLs for JIRA, a project management service provided by Atlassian, that showed Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’ aerospace manufacturer and sub-orbital spaceflight services company, discussing a competitor and the failure of speed sensors, calibration equipment, and manifolds. Other JIRA customers exposed included security company FireEye, BuzzFeed, NBCdigital, AlienVault, CardinalHealth, TMobile, Reddit, and UnderArmour.

Clearly, this is not good. But how did it happen?

-

DataSpii revealing Raven in late March, about a week before it became widely known as a Tesla code name.

-

The history of Tesla pages being opened.

-

Trend Micro project management issues from a non-public domain.

-

Symantec was exposed by DataSpii as well.

-

Project management issues from a non-public FireEye domain.

-

Browsing data published for Blue Origin showing project management items and non-public subdomains.

-

Atlassian domains.

-

One of thousands of mailers showing the names and addresses of car buyers, along with how many more payments they had left and the identification numbers of their vehicles.

-

Travel itineraries containing passengers’ full names and email addresses are a common DataSpii occurrence.

The data spy

The term DataSpii was coined by Sam Jadali, the researcher who discovered—or more accurately re-discovered—the browser extension privacy issue. Jadali intended for the DataSpii name to capture the unseen collection of both internal corporate data and personally identifiable information (PII). (Ars has more technical details about DataSpii here.)

As the founder of Internet hosting service Host Duplex, Jadali first looked into Nacho Analytics late last year after it published a series of links that listed one of his client domains. Jadali said he was concerned because those URLs led to private forum conversations—and only the senders and recipients of the links would have known of the URLs or would have the credentials needed to access the discussion. So how had they ended up on Nacho Analytics?

Jadali suspected that the links were collected by one or more extensions installed on the browsers of people viewing the specialized URLs. He forensically tested more than 200 different extensions, including one called “Hover Zoom”—and found several that uploaded a user’s browsing behavior to developer-designated servers. But none of the extensions sent the specific links that would later be published by Nacho Analytics.

Still curious how Nacho Analytics was obtaining these URLs from his client’s domain, Jadali tracked down three people who had initial access to the published links. He correlated time stamps posted by Nacho Analytics with the time stamps in his own server logs, which were monitoring the client’s domain. That’s when Jadali got the first indication he was on to something; two of his three users told him they had viewed the leaked forum pages with a browser that used Hover Zoom.

Web searches such as this one have reported the extension’s earlier history of data collection. Suspicious that Hover Zoom might be doing the same thing again, Jadali set out to more rigorously test the extension.

He set up a fresh installation of Windows and Chrome, then used the Burp Suite security tool and the FoxyProxy Chrome extension to observe how Hover Zoom behaved. This time, though, he found no initial sign of data collection, so he remained patient. Then, he said, after more than three weeks of lying dormant, the extension uploaded its first batch of visited URLs. Within a couple of hours, he said, the visited links, which referenced domains controlled by Jadali, were published on Nacho Analytics. Soon after, each URL was visited by a third party that often went on to download the page contents.

Jadali eventually tested browser extensions for Firefox and also set up test machines running both macOS and the Ubuntu operating system. In the end, he said, the extensions that he found to have collected browsing histories that later appeared on Nacho Analytics include:

- Fairshare Unlock, a Chrome extension for accessing premium content for free. (A Firefox version of the extension, available here, collects the same browsing data.)

- SpeakIt!, a text-to-speech extension for Chrome.

- Hover Zoom, a Chrome extension for enlarging images.

- PanelMeasurement, a Chrome extension for finding market research surveys

- Super Zoom, another image extension for both Chrome and Firefox. Google and Mozilla removed Super Zoom from their add-ons stores in February or March, after Jadali reported its data collection behavior. Even after that removal, the extension continued to collect browsing behavior on the researcher’s lab computer weeks later.

- SaveFrom.net Helper a Firefox extension that promises to make Internet downloading easier. Jadali observed the data collection only in an extension version downloaded from the developer. He did not observe the behavior in the version that was previously available from Mozilla’s add-ons store.

- Branded Surveys, which offers chances to receive cash and other prizes in return for completing online surveys.

- Panel Community Surveys, another app that offers rewards for answering online surveys.

While Jadali can’t be certain how Nacho Analytics obtained URLs for pages that can only be accessed by people authorized by companies like Apple, Tesla, Blue Origin, or Symantec, the most likely explanation is that one or more of them had a browser with an affected extension. Jadali has confirmed with four affected companies that employees did, in fact, have one or more of the extensions installed. Palo Alto Networks also confirmed to Ars that browsers inside its network used an affected extension. All five companies have since removed the extensions. Google, citing violations to its terms of service, has also removed the six extensions it hosted in its Chrome Web Store.

Ars contacted a small sample of affected companies, including Apple, Symantec, FireEye, Palo Alto Networks, Trend Micro, Tesla, and Blue Origin. Symantec, Trend Micro, and Palo Alto Networks were the only ones who provided a comment.

Symantec’s statement read: “We want to thank the researcher for alerting us to this issue and sharing his findings. We have taken immediate steps to remediate this issue.” Trend Micro officials said: “Trend Micro appreciates being made aware of this and has remedied the issue.” A Palo Alto Networks representative wrote: “On the day we were notified of the issue, Palo Alto Networks deleted the browser extensions and blocked the outbound traffic associated with the add-on extensions to prevent any further potential impact.”

Investigating DataSpii over the past six months has eclipsed Jadali’s full-time job and much of his personal life.

Jadali said the new vocation has so far cost him nearly $30,000 in personal expenses, since the research is not tied to his responsibilities at Host Duplex. Jadali estimates that about 60% of the cost has been in fees from Nacho Analytics. The rest has been for travel and for various consultants.

“It became my number one priority,” he said. “Almost as if it was out of my control.”

Reading the fine print

Principals with both Nacho Analytics and the browser extensions say that any data collection is strictly “opt in.” They also insist that links are anonymized and scrubbed of sensitive data before being published. Ars, however, saw numerous cases where names, locations, and other sensitive data appeared directly in URLs, in page titles, or by clicking on the links.

The privacy policies for the browser extensions do give fair warning that some sort of data collection will occur. The Fairshare Unlock policy, for example, says that the extension “collects your digital behavior data and shares it with 3rd parties to enable better survey targeting and other market research activities.” (This and other policies mentioned in this article were recently taken down.)

The collected information expressly includes “URLs visited, data from URLs loaded and pages viewed, search queries entered, social connections, profile properties, contact details, usage data, and other behavioral, software, and hardware information.” At the same time, the policy promises that Fairshare will take steps to anonymize the data.

“For our primary use-case of research, PII scrubbers attempt to remove all personally identifiable information before analysis and archiving,” the Fairshare Unlock policy states. “Individual users are regularly re-assigned randomly generated identifiers which, when combined with PII scrubbing, provides anonymity.”

Privacy policies for SpeakIt!, PanelMeasurement, Hover Zoom, Panel Community Surveys, and Branded Surveys contain language that’s largely identical to that cited above. Savefrom.net’s policy also makes clear it will collect the “URL of the particular Web page you visited.” (The policy for Super Zoom is no longer available.) Below are images that some of the extensions display when being installed:

-

Fairshare Unlock permissions.

-

Hover Zoom permissions.

-

Speak It! permissions.

-

PanelMeasurement permissions.

-

The opt-in page for PanelMeasurement.

Nacho Analytics, for its part, has this to say in a YouTube promotion, which starts out asking “Is this legal?”

Yes, it’s 100 percent legal and completely complies with google’s terms of service. We aren’t actually hacking google or anyone’s google analytics account, though it might seem that way. Instead we are gathering data from millions of opt in users, individuals from around the world that agreed to share their browsing data anonymously. Nacho analytics scrubs this data so all personal information is deleted and so it’s GDPR compliant. This type of data gathering is far from a new innovation. On the contrary, it’s kind of how the Internet runs.

(GDPR is a reference to the strict General Data Protection Regulation that went into effect in the European Union 26 months ago. The video was removed from YouTube after this post went live.)

Jadali’s research found that Fairshare Unlock, PanelMeasurement, SpeakIt!, Hover Zoom, Branded Surveys, and Panel Community Surveys did redact some information on end users’ computers before sending it to the developer-designated servers. But he said that an examination of data packets sent to the servers and links published on Nacho Analytics makes it clear that not all types of sensitive information were removed. Redaction seemed to happen only when Web developers use certain query string parameters in their URLs.

As the image above shows, strings that used “lastname=x” seemed to successfully cause last names to be replaced with asterisks. Strings that used “passengerLastName=y,” however, were not removed. None of Jadali’s research shows that Super Zoom or SaveFrom.net Helper performed any redactions at all.

What’s more, some links published by Nacho Analytics contain what appear to be the personal information of real people. Examples of such personal information included passenger names in links from airline Southwest.com, pick-up and drop-off locations of people using the Uber.com website (but not the phone app) to hail rides, and email addresses from Apple’s password reset service. While Jadali redacted sensitive information from the following screenshots, none of it was removed from the links published by Nacho Analytics.

-

Sam Jadali

-

Sam Jadali

-

Sam Jadali

What’s more, even when the URLs published by Nacho Analytics removed names, social security numbers, or other sensitive information, clicking on the links often led to pages that revealed the same redacted information.

Meet the DataSpii players

DDMR

Google’s Chrome Web Store lists the developer of PanelMeasurement as DDMR.com with a mailing address in Walnut, California. The store doesn’t identify the developer of Fairshare Unlock, Hover Zoom, SpeakIt!, or Super Zoom, but the privacy policy for Fairshare Unlock also lists DDMR.com and the same Walnut, California, mailing address in a Contact Us section. The policies for Hover Zoom, SpeakIt!, and Panel Community Surveys also contain language and organization almost identical to those for the PanelMeasurement and Fairshare Unlock extensions.

Another link to DDMR: domains that received browsing data from all eight of the extensions resolved to the same two IP addresses—54.160.162.145 and 52.54.192.223. This page from SSL Labs, a research project by security firm Qualys, shows that 54.160.162.145 is tied to a security certificate belonging to DDMR domain ddmr.com (viewers first must click the “click here to expand” for certificate #2).

This LinkedIn profile lists Christian Rodriguez as the founder and CEO of DDMR. A 2015 article—reporting an earlier round of data collection by Chrome extensions—identifies Rodriguez as working in business development for Fairshare Labs. Fairshare Labs’ contact page lists the same Walnut, California, mailing list.

Rodriguez told me that Fairshare Labs is an abandoned project and that Fairshare Unlock is no longer actively developed (although he said it does continue to receive security and GDPR compliance updates). He pointed to the bottom of this page, which he said provides “very clear, pre-installation disclosure to users.”

Rodriguez described DDMR as a “passive metering technology company” that provides market research companies with “passive metering browser extensions that they distribute to their research panelists.” He went on to write in an email:

Our customers are responsible for recruiting end-users into their panels and directing them to our landing pages.

It is our responsibility to (1) ensure that we provide end-users with clear disclosure of what data is collected and how it is used, and (2) receive appropriate consent. Once consent is given, we collect the behavioral data, scrub it for sensitive information like phone numbers, social security numbers, credit card numbers, and email addresses, and then make it available to market researchers to use in their research.

If it is brought to our attention that sensitive information is leaking, we immediately take action to improve our filters and eliminate that data from our dataset.

Responsible use of behavioral data allows market researchers and the companies they serve to build better products and experiences for consumers, but it is necessary to recognize the value of this data in the context of its potentially sensitive nature.

He declined to say if Nacho Analytics was a customer, business partner, or had any other relationship with DDMR.

Nacho Analytics

Nacho Analytics, meanwhile, promises to let people “see anyone’s analytics account” and to provide “Real-Time Web Analytics For Any Website.” The company charges $49 per month, per domain, to monitor any of the top 5,000 most widely trafficked websites, although certain domains—including those for Google, YouTube, Facebook, and others—aren’t available for monitoring. For sites below this premium threshold, it costs $49 per month to monitor one domain, $99 per month for up to five domains, and $149 per month for up to 10 domains.

Once someone signs up, Nacho Analytics uses a Google-provided programming interface to deliver data to a Google Analytics account designated by the user. Ars installed several extensions identified by Jadali, visited sites with long-pseudorandom strings in them, and then observed Nacho Analytics populating those unique URLs into the designated Google Analytics page.

-

One booking.com page with a specific string in the URL

-

A second one. Both are viewed using a browser that has four DataSpii extensions installed.

-

Both pages are soon published.

The previously mentioned video promoting Nacho Analytics on YouTube says that the service is “100-percent legal and completely complies with Google’s terms of service.” The video also asserts that the Nacho Analytics service is “GDPR compliant.”

In an interview, Nacho Analytics founder and CEO Mike Roberts reiterated that the service is fully GDPR compliant and that the millions of people whose data is collected have expressly agreed to this arrangement.

“You absolutely do” click an agree button, Roberts said of all users whose data is published. What’s more, he said, “we spend quite a bit of time processing every URL that we see to remove all the personally identifiable information.” Ars has confirmed that in many cases, the URLs published by Nacho Analytics have had names, Social Security numbers, and other personal information removed. However, Ars was also able to find numerous instances of names and other personal information remaining in published URLs.

Roberts said that he was unaware Nacho Analytics published links to webpages hosting tax returns, Nest Videos, car buyer information, and an extensive amount of other personally identifiable information. Nacho Analytics already excludes domains for Google, Facebook, YouTube, and many other services out of privacy concerns, he said, and may exclude others.

“Your report is personally disturbing to me–and [publishing sensitive data] is definitely not the purpose of Nacho Analytics,” he said. “We work hard to remove personally identifiable information from URLs and page titles, and exclude sites with serious security issues. When we learn of a new issue, we have a system to remove it immediately. We’ve stopped all new sign-ups for Nacho until we can get more information on this issue. If you give me a list of the sites that have these issues, we’ll immediately disable those sites and work on a permanent solution.”

He also pushed back on the idea that Nacho Analytics had ever been used by customers to harvest sensitive information. Jadali, he claimed, was the only one who had done so. (He also claimed that Jadali had violated Nacho Analytics’ terms of service in doing the research.)

“Jadali looked at hundreds of websites, only a tiny fraction of which any legitimate Nacho Analytics customer ever viewed,” he said. “In fact, none of the sites with the issues you’ve made me aware of have been viewed by any legitimate Nacho Analytics customer.”

But Roberts defended the basic practice of publishing links that, when clicked, lead to private data—so long as that data isn’t viewable in the URL itself as published by Nacho Analytics.

He put it this way:

Those pages are available. It’s just that you didn’t know how to discover them. This is just something that you’re now able to see that you weren’t able to see before. But we’re not creating a loophole. There’s no backdoor or anything. We’re just showing links that you didn’t know about before and maybe weren’t indexed, but they do exist…

That link by obfuscation thing, I don’t like it. I wish it didn’t exist because I definitely don’t want to be enabling anybody to do anything bad, only good. I’m trying to create good things in the world. And there’s the opportunity there for some people to do some damage.

Roberts said he was also unaware that Nacho Analytics was publishing links and page titles from the non-public, internal networks of companies. But, while he questioned the analytics value of this data, he didn’t necessarily think publishing it was a bad thing.

“I don’t think I personally see much value in it,” he said. “But just because a company may want to keep it private, I’m not sure that’s where the best value is.”

He said he had never heard of any of the extensions that Jadali had identified as collecting data that later ended up on Nacho Analytics, but he declined to identify any software that collects end-user browsing data, nor would he name any companies that Nacho Analytics works with to obtain this data. (In a later email, he clarified that the data “comes from third-party data brokers. We certainly didn’t invent the method of data collection.”)

“Using Nacho to look at private information or to try to hack into websites is an explicit violation of our terms of use,” Roberts added. “[Nacho is] a marketing product that puts small businesses and entrepreneurs on a level playing field with large corporations that have and will continue to have access to this type of data.”

“Honestly, I think you have the wrong villain here.”

On July 8, five days after Google remotely disabled the extensions Jadali had reported, Roberts said on Twitter that Nacho Analytics “had an upstream data outage.” A day later, Roberts said Nacho Analytics’ “data partner has ended operations.” Shortly after that, the Nacho Analytics front page said the service was “halting all access to any potentially sensitive data.”