reader comments

324 with 101 posters participating

The European Space Agency (ESA) yesterday took action to avoid a collision with a SpaceX broadband satellite after a bug in SpaceX’s on-call paging system prevented the company from getting a crucial update.

“For the first time ever, ESA has performed a ‘collision avoidance maneuver’ to protect one of its satellites from colliding with a ‘mega constellation,'” the ESA said on Twitter. The “mega constellation” ESA referred to is SpaceX’s Starlink broadband system, which is in the early stages of deployment but could eventually include nearly 12,000 satellites.

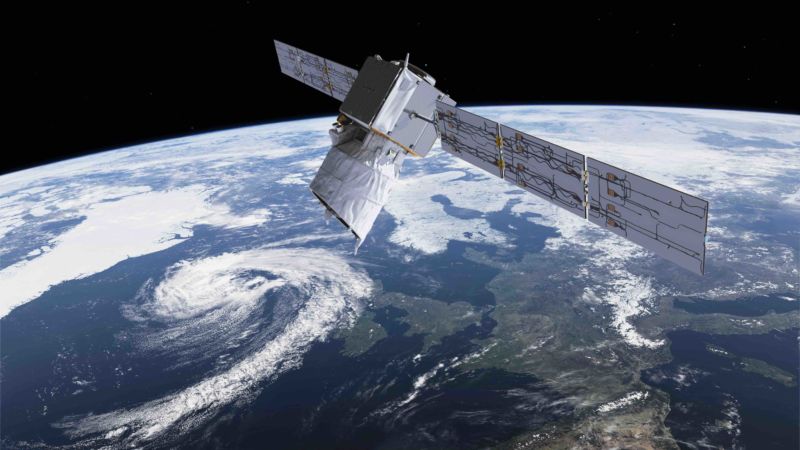

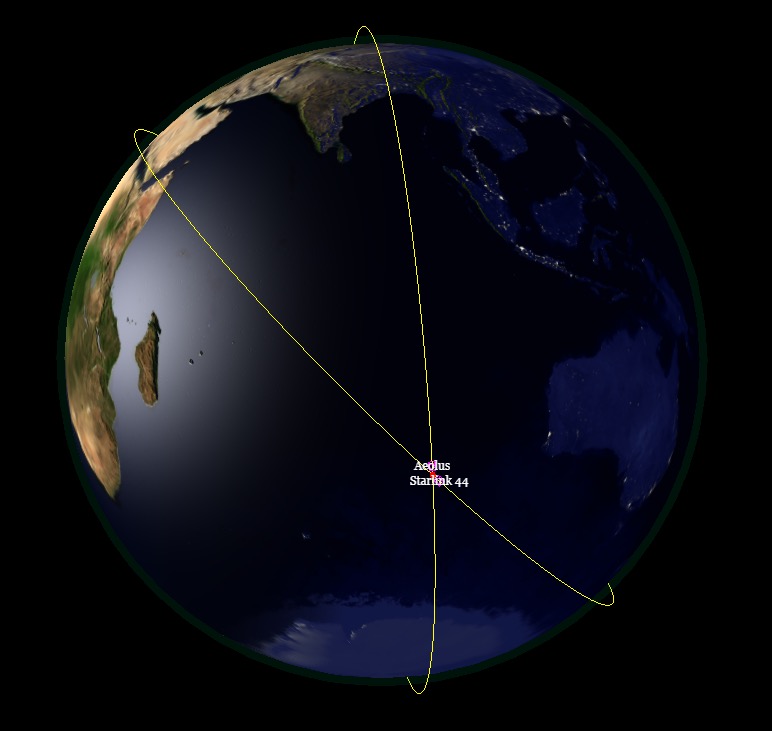

Action had to be taken because the ESA’s Aeolus satellite and a Starlink satellite were on a course that carried more than a 1-in-10,000 chance of a collision. According to the ESA, the Earth-observation satellite Aeolus “fired its thrusters, moving it off a collision course with a SpaceX satellite in their Starlink constellation.”

SpaceX paging system failed

A Forbes article yesterday was originally headlined, “SpaceX refused to move a Starlink satellite at risk of collision with a European satellite,” and the piece included quotes from ESA Space Debris Office chief Holger Krag:

“Based on this [collision risk] we informed SpaceX, who replied and said that they do not plan to take action,” says Krag, who said SpaceX informed them via email—the first contact that had been made with SpaceX, despite repeated attempts by Krag and his team to get in touch since Starlink launched. “It was at least clear who had to react. So we decided to react because the collision was close to 1 in 1,000, which was ten times higher than our threshold.”

SpaceX explained in a statement today that it didn’t initially take action because of early estimates that the risk of collision was much lower than it turned out to be. SpaceX said it would have coordinated with ESA to avoid a collision once the estimates got worse, if only the paging-system bug hadn’t prevented SpaceX from getting an update on the collision probability. SpaceX said it is trying to fix the bug to prevent such mishaps in the future.

Here’s the full statement that SpaceX provided to Ars:

Our Starlink team last exchanged an email with the Aeolus operations team on August 28, when the probability of collision was only in the 2.2e-5 range (or 1 in 50k), well below the 1e-4 (or 1 in 10k) industry standard threshold and 75 times lower than the final estimate. At that point, both SpaceX and ESA determined a maneuver was not necessary. Then, the US Air Force’s updates showed the probability increased to 1.69e-3 (or more than 1 in 10k) but a bug in our on-call paging system prevented the Starlink operator from seeing the follow on correspondence on this probability increase—SpaceX is still investigating the issue and will implement corrective actions. However, had the Starlink operator seen the correspondence, we would have coordinated with ESA to determine the best approach with their continuing with their maneuver or our performing a maneuver.

We contacted Krag and the ESA press office, and they referred us to an article published today on the ESA website. Krag made it clear that he does not blame SpaceX, but he said the incident highlights a need for better systems to prevent collisions.

“No one was at fault here, but this example does show the urgent need for proper space traffic management, with clear communication protocols and more automation,” Krag said in the ESA article. “This is how air traffic control has worked for many decades, and now space operators need to get together to define automated maneuver coordination.”

Despite the paging-system bug, SpaceX’s initial statement that it wouldn’t move its satellite apparently turned out to be helpful. “Contact with Starlink early in the process allowed ESA to take conflict-free action later, knowing the second spacecraft would remain where models expected it to be,” the ESA said.

ESA plans to automate collision avoidance

The ESA said on its website that it “plans to invest in technologies required to automatically process collision warnings, coordinate maneuvers with other operators, and send the commands to spacecraft entirely automatically.”

In his communication with Forbes, Krag said that “There are no rules in space. Nobody did anything wrong. Space is there for everybody to use… Basically on every orbit you can encounter other objects. Space is not organized. And so we believe we need technology to manage this traffic.”

Starlink and similar broadband networks will dramatically increase the number of satellites in space, raising the risks of space debris and collisions, as we’ve previously written. SpaceX has touted its collision-avoidance technology, with CEO Elon Musk saying in May that Starlink satellites will “automatically maneuver around any orbital debris.”

Aeolus orbits at an altitude of 320km. “Krag said this was the first collision avoidance maneuver for Aeolus since its launch a little more than one year ago,” a Space News article yesterday said. “Conjunctions are rare at that low altitude, he noted, and in general most conjunctions are with debris, which constitute about 90 percent of the objects currently tracked in orbit.”

With yesterday’s collision-avoidance action, the ESA said its experts determined that the safest option for Aeolus was to increase its altitude to pass over the SpaceX satellite. The ESA said it completed the maneuver “about 1/2 an orbit before the potential collision” by raising Aeolus’ altitude by 350 meters.

The ESA warned that today’s manual collision-avoidance system “will become impossible” because of the thousands of new satellites being deployed by Starlink and other broadband clusters. “Collision avoidance maneuvers take a lot of time to prepare—from determining the future orbital positions of functioning spacecraft, to calculating the risk of collision and the many possible outcomes of different actions,” the ESA said.

But the ESA has a plan.

“ESA is preparing to automate this process using artificial intelligence,” the agency said. “From the initial assessment of a potential collision to a satellite moving out of the way, automated systems are becoming necessary to protect our space infrastructure.”

Coordination between entities should also be automated, Krag told Ars.

“I think that we need to get away from the current practice of operator exchange through email and move towards standardized computer-based coordination,” Krag said. “This could follow a commonly agreed protocol, with a clear standard for which information is to be exchanged (orbit information, maneuver plans, constraints of the platform, etc…). In an Internet-of-Things-like approach, the best maneuver plan could thus be ‘negotiated’ between the involved operator centers without human interaction.”