At the end of February, the US National Transport Safety Board presented its findings from a two-year investigation into a fatal crash involving a Tesla Model X driving on Autopilot. Given the current state of the tech, it served as another reminder of how dangerous self-driving technologies can be.

For years, people have highlighted how misleading it is to use words like “autopilot” to describe a range of cars that have varying degrees of autonomy, and yet nothing has changed.

As EVs and self-driving cars continue to evolve, the word autopilot is taking on new meaning and is being applied in entirely new contexts. No longer is autopilot purely an aviation term, it’s being used as catch-all for high-level driver assistance features in all kinds of vehicles.

This semantic shift is having dangerous consequences that shouldn’t be overlooked.

[Read: The 6 levels of autonomous driving, explaind as fast as possible]

A brief history of automatic pilots

The word autopilot first entered the English language in the early 1900s alongside the creation of the “automatic pilot,” invented by New York-based electronics and navigation firm, the Sperry Corporation.

In 1912, the company demonstrated its “automatic pilot” system by flying over the Seine in Paris as onlookers lined the river banks. There were two pilots in the plane: Emil Cachin a French mechanic, and American aviator and inventor Lawrence Sperry. During the demonstration, hands were lifted from the controls and held aloft, the pilots even walked out onto the wings to show how the plane could balance itself and maintain course. The crowd was amazed, most likely.

The systems connected the hydraulics that control the plane’s elevators and rudders to its navigational systems. Doing this enabled the plane to maintain course and elevation all on its own. It’s kind of where Level 2 self-driving systems are now, but more on that later.

Despite massive developments in aviation autopilot systems, one thing has remained: Human pilots.

Autopilot systems were never designed to replace pilots entirely, but rather, reduce their workload by providing a high level of assistance to make flying long distances less taxing.

Pilots are highly trained specialists in their field — car drivers, generally speaking, are not. Yet when it comes to self-driving cars, drivers are seemingly very willing to place all their faith in the tech despite having no formal training with the technology — and it’s having devastating consequences.

The incident

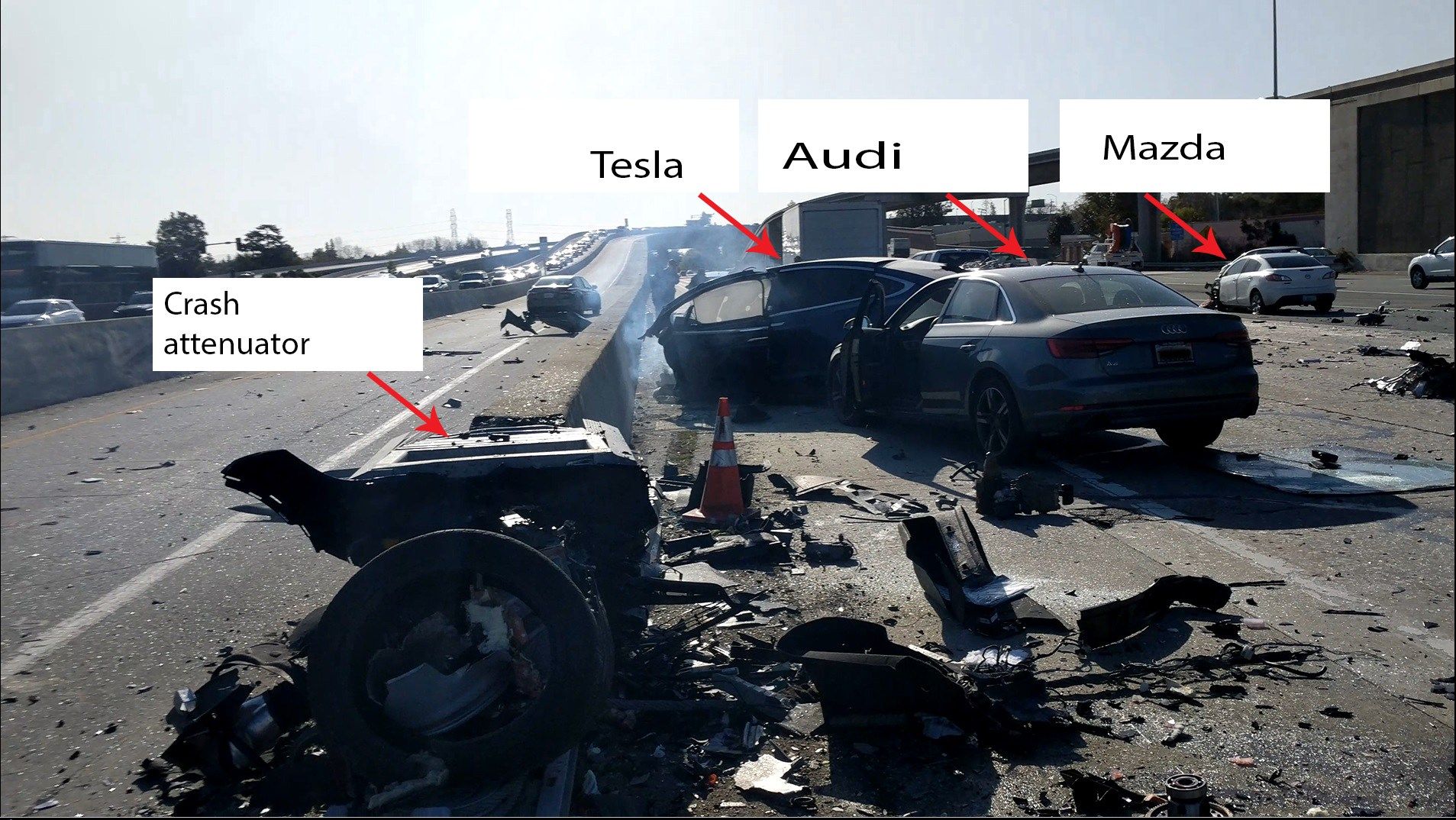

Take the recently closed case of Apple employee Walter Huang. The crash of Huang’s Model X has been one of the most debated road traffic incidents involving a vehicle with supposed “self-driving” capabilities in recent years.

In 2018, Huang’s Tesla Model X was driving on Autopilot when it crashed. Huang’s use — and Tesla’s implementation — of Autopilot systems were deemed, above all else, to be the main contributing factors leading to the incident.

Before the crash, Autopilot had been active for 18 minutes. Throughout his journey, Huang’s vehicle alerted him to realign his concentration to the road and place his hands back on the steering wheel.

At the time of the crash, Huang was believed to have been playing a video game on his mobile phone. He was transported to hospital where he later died from his injuries. It appears that Huang was treating his Tesla like a fully autonomous vehicle when it isn’t.

Teslas aren’t even close to being fully autonomous vehicles.

Self-driving cars do not exist

Speaking about the incident, NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt said: “The car involved in this crash was not a self-driving car. You cannot buy a self-driving car today. We’re not there yet.”

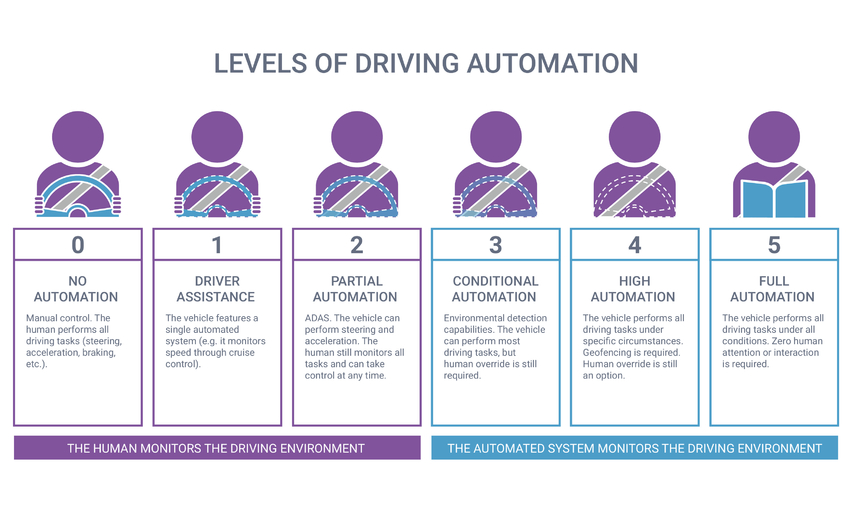

In reality, Tesla’s Autopilot systems are Level 2, meaning they can fully control the car, but they cannot interpret the world to actually drive the vehicle safely and autonomously. In Level 2 systems, the driver must remain alert and pay attention to the road at all times, ready to take control at any moment.

[Read: The 6 levels of autonomous driving, explained as fast as possible]

Autonomous driving is possible in some forms, though. Google Waymo is considered a Level 4 system, but it can only drive in fully autonomous mode in a specific area and below 30 mph (48 km/h). While Waymo regularly makes headlines, it’s only operating in Phoenix, Arizona at the moment.

There’s a substantial difference between Level 2 and Level 4 systems; in fact, there are six different levels of autonomous driving technology. Each level is subtly nuanced from the next, to group them all as one is heavy-handed. For example, the first three levels (Zero through two) don’t possess any real autonomy at all. So why are we even putting them on a scale of automation?

Indeed, it seems the public generally isn’t aware of these nuances either.

An AAA survey, from 2018, found that 40% of Americans expect partially automated driving systems with names like Autopilot, ProPILOT, or Pilot Assist, to have the ability to drive the car by itself. This is despite countless warnings in vehicle user manuals that specifically say these systems are not designed for full automation.

What’s more concerning though, these systems rarely include any technology to prevent their misuse.

No safeguards against Autopilot misuse

As Sumwalt said at the hearing, there is a severe lack of “safeguards to prevent foreseeable misuse of the technology.” The NTSB has been aware of this for a while, and is trying to get manufacturers to try harder, but Tesla isn’t playing ball.

Back in 2017, the NTSB made a series of recommendations to all manufacturers to develop measures to prevent the misuse of their “autonomous” driving technologies.

Five manufacturers replied promptly, saying they were working to implement the recommendations. Tesla, on the other hand, ignored the NTSB’s communications.

At the time of the hearing, it had been over 880 days since the NTSB first contacted Tesla and it’s still waiting to hear what the EV maker is doing to improve the safety of its self-driving technologies.

This is perhaps the defining point in every fatality that’s occurred in a Tesla whilst Autopilot was engaged. The system can still work even if the driver isn’t paying attention.

Too much faith in technology

Like many other Teslas involved in accidents where Autopilot was in use, Huang seemingly trusted the technology more than he should have been allowed to. Other similar incidents appear to indicate that drivers also thought they had a truly autonomous vehicle, when they did not.

The first death involving a Tesla Model S whilst on Autopilot (Level 2 systems) happened in May 2016 when a Model S impacted with a truck crossing its path. According to a blog post from Tesla at the time, the incident was a result of both car and the driver failing to distinguish the white truck against a bright sky. This implies that the driver was paying attention, but because Tesla’s have no way of tracking attention, we can’t know for sure.

Later in 2016, Chinese media reported a similar fatality when another Tesla driver struck the back of a road sweeping truck that was clearing the central reservation. It’s believed Autopilot was in use at the time of the accident, and like the previous case, it seems the system failed to “see” the vehicle ahead in enough time to apply the brakes.

In dashcam footage from the incident, despite the haze that supposedly prevented Autopilot from working as it should, the truck can be seen in the distance. Again, it seems the driver wasn’t paying full attention to road and driving according to the prevailing road conditions. The footage can be watched below, viewer discretion is advised.

In March 2019, similar to both previous cases, another Tesla driver was killed when their vehicle failed to yield to a truck crossing its path on the highway. According to a police report at the time, the driver enabled Autopilot just 10 seconds before the crash, for about eight seconds before impact, the driver didn’t have their hands on the steering wheel.

The common theme in all of these fatal road traffic incidents was that drivers overestimated the capabilities of their car’s “self-driving” technology and didn’t pay full attention to the road and drive according to the conditions.

Despite these cases, Tesla has remained adamant that its vehicles are safer than conventional cars.

Lack of experience and clarity is dangerous

Danish insurer Topdanmark found that EVs were involved in 20% more accidents than conventional cars. It found that Teslas were involved in up to 50% more accidents.

In many cases these were low speed, low impact incidents where cars drove into bollards, pillars, and other road furniture. The insurer pointed out the quick and immediate acceleration of EVs as the most likely reason behind these incidents.

Research conducted by French insurance company, AXA, last year, found high-end EVs — like Tesla’s Model S — to be 40% more likely to cause accidents than internal combustion engine vehicles.

Like Topdanmark, AXA says, the additional risk is a result of EVs’ quick acceleration and because drivers aren’t as experienced with the new technology in these kinds of vehicles.

While these pieces of research don’t directly relate to Autopilot-like systems, it does highlight how drivers need to get used to, learn, and adapt to new technologies in order to drive safely. In all the Autopilot fatalities, drivers overestimated and failed to adapt accordingly to the technology.

Heikki Lane, vice president of product at Cognata, a company that specifically tests advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) in virtual environments to understand how they might operate in the real world, told me that as “ADAS adoption [is] continuing to increase, confusion is only becoming more common.”

It seems the lack of familiarity might be a larger factor in EV self-driving accidents than has been acknowledged. It might also go some way to explaining why drivers put so much faith in the tech: They don’t fully understand its capabilities and limitations.

That said, it’s not entirely the fault of drivers. From manufacturer to manufacturer, the industry lacks clarity. “The inconsistency in the brand-specific names used to market ADAS systems has been creating consumer confusion for years,” Lane told TNW.

In some cases, advanced driver aids, like automatic emergency braking, have been marketed under as many as 40 different names, Lane said, referencing a 2019 AAA study.

Confusion costs lives

There are two ways to look at this. For manufacturers, using workds like Autopilot supposedly helps them differentiate their product against the competition. But it also obscures the true nature of the features by wrapping them in misleading futuristic-sounding marketing language.

For drivers, it ends up being unclear what words like Autopilot, ProPilot, Pilot Assist, and Full Self-driving actually translate to in terms of vehicle capabilities.

This combination of vaguely and inconsistently marketed “self-driving” systems, and the lack of driver familiarity is having devastating consequences. It’s clear using the terms like “Autopilot” as a generic catch-all for high level driver aids is problematic.

At the very least, it’s time we stop referring to Level 2 cars as self-driving, and refer to them for what they are: vehicles with heavily marketed driver aids. It’s time the industry adopted consistent terminology that better describes what these systems actually do. They should also make it impossible to use these technologies without paying full attention to the road.

Drivers deserve safety, not chaos and confusion.

Read next: Amazon, Netflix, and Facebook: Say hello to ‘stay-at-home’ tech stocks

Corona coverage

Read our coverage on how the tech industry is responding to the coronavirus here.

For tips and tricks on working remotely, check out our Growth Quarters articles here or follow us on Twitter.