reader comments

202 with 111 posters participating

Millions of law enforcement documents—some showing pictures of suspects, bank account numbers, and other sensitive information—have been published on a website that holds itself out as an alternative to WikiLeaks, according to security news website KrebsOnSecurity.

DDOSecrets, short for Distributed Denial of Secrets, published what it said were millions of documents stolen from more than 200 law enforcement groups around the country. Reporter Brian Krebs, citing the organization National Fusion Center Association (NFCA), confirmed the validity of the leaked data. DDOSecrets said the documents spanned at least a decade, although some of the dates in documents suggested a timespan twice as long.

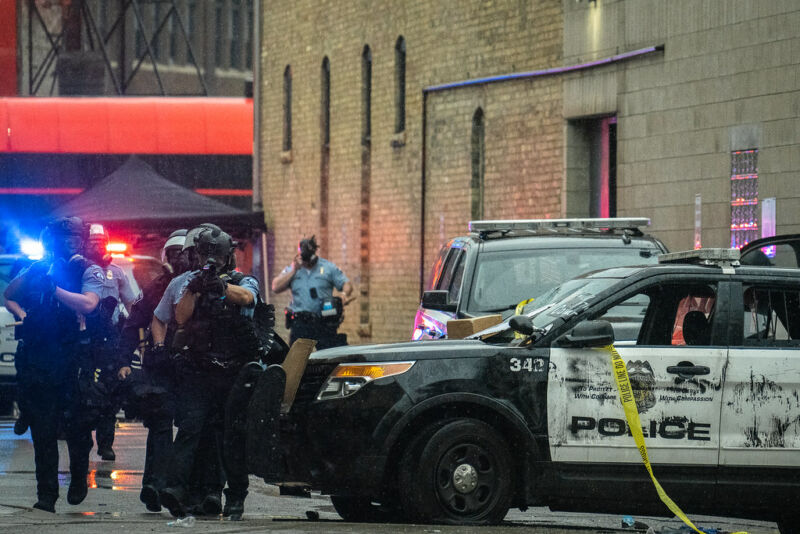

Dates on the most recent documents were from earlier this month, suggesting the hack that first exposed the documents happened in the last three weeks. The documents, which were titled “BlueLeaks,” were published on Friday, the date of this year’s Juneteenth holiday celebrating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans in the Confederacy. BlueLeaks had special significance in the aftermath of a Minneapolis police officer suffocating a handcuffed Black man to death when the officer placed his knee on the man’s neck for 8 minutes and 45 seconds.

Over the weekend, critics of police abuse took to social media to celebrate the leak and display documents that purportedly came from it. Some of them included:

- An FBI document identifying Twitter posts that “threaten[ed] law enforcement supporters’ safety as of May 2020.”

- Motorcycle gangs that opportunistically used protests to pose as members of the antifa movement inciting riots and for the gang to “move large amounts of heroin into the Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, area.”

- Law enforcement personnel tracking potential protesters’ use of SnoopSnitch, an app that detects when IMSI catchers are being used to monitor cell phone data.

The link hosting the data only sporadically loads and, more often than not, times out before loading the index page. When it does display, the page organizes leaked documents both by the law enforcement agency they came from and often by names of individuals purportedly associated with a document. Once again, clicking on a link more often than not fails to load the document. BitTorrent links have also been made available, but they too fail.

What that means is that most of the world has only seen a small portion of the leak in tiny snippets without the ability to analyze the leak in its entirety first hand.

The leaks, according to Krebs, are the result of a hack on the server of Netsential, a Houston-based Web development firm that caters to law enforcement groups, among other customers. Much of the pilfered data was distributed through law enforcement “fusion centers” across the United States that act as hubs for federal, state, and local agencies to share information. Krebs also quoted a former assistant secretary of policy at the US Department of Homeland Security, saying that some of the exposed data could endanger the safety of individual sources by identifying them publicly.

In an article published by Wired, however, DDOSecrets co-founder Emma Best said that they (Best’s pronoun) spent a week prior to leak publication removing about 50 gigabytes of material disclosing sensitive details about crime victims, children, and information on unrelated private businesses, health care, and retired veterans’ associations.

“It’s the largest published hack of American law enforcement agencies,” Best told the publication in a series of text messages. “It provides the closest inside look at the state, local, and federal agencies tasked with protecting the public, including [the] government response to COVID and the BLM protests.”