reader comments

58 with 46 posters participating

In our 5,000 word piece on “DataSpii,” we explained how researcher Sam Jadali spent tens of thousands of dollars investigating the murky Internet ecosystem of browser extensions that collect and share your Web history. Those histories could end up at sites like Nacho Analytics, where they can reveal personal or corporate data.

Here, we want to offer more detail for the technically curious reader on exactly how these browser extensions work—and how they were discovered.

Obscurity

Discovering which browser extensions were responsible for siphoning up this data was a months-long task. Why was it so difficult? In part because the browser extensions appeared to obscure exactly what they were doing. Both Hover Zoom and SpeakIt!, for instance, waited more than three weeks after installation on Jadali’s computers to begin collection. Then, once collection started, it was carried out by code that was separate from the extensions themselves.

One example: immediately after an installation on February 5, 2019, both extensions contacted developer-designated servers and reported their installation time, installation version, current version, and unique extension ID. On February 15, the extensions received an automatic update, but they still didn’t collect any browsing history. Then, on March 1, both extensions received a second automatic update.

Almost immediately, the extensions again contacted developer-controlled servers and reported the unique ID of the extension, installation time, and current version. About one second later, the extensions received a 156KB payload, with 150KB of this being stored not in the extension folder, but in the Chrome browser system profile (in Jadali’s case, the file was located at C:UsersAdministratorAppDataLocalGoogleChromeUser DataDefaultFile System�02p�0�0000000).

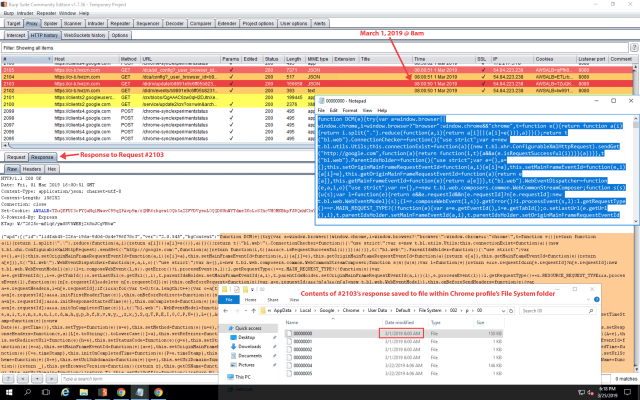

The Hover Zoom extension can be seen downloading the 156KB payload in request 2103 of the following packet capture:

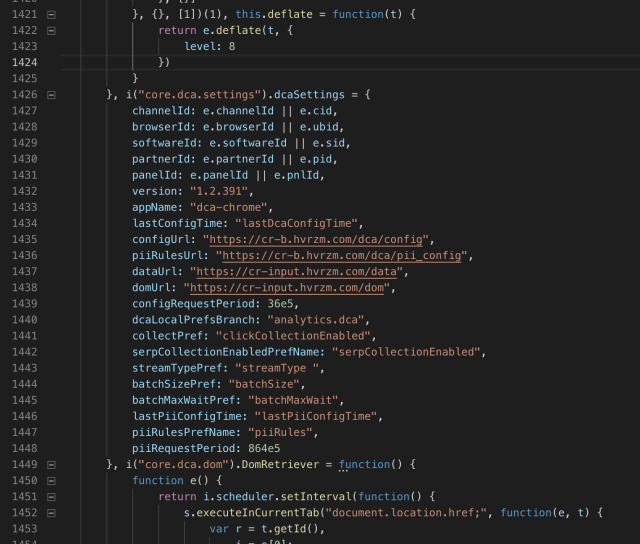

This payload contained a minified JavaScript file that was responsible for collecting a user’s browsing data and sending it to a developer-controlled server. The contents of the file are shown in the figure below:

The JavaScript file downloaded by the SpeakIt! Extension looked substantially the same; it also mentions the same cr-b.hvrzm.com host name found in the Hover Zoom file. These JavaScript files, because they’re stored in the Chrome profile and don’t update the actual extension that downloaded them, make it substantially harder for investigators—both inside and outside of Google—to detect the data collection.

“If people examine the extension itself, they’re not going to see that data collection instruction set,” Jadali told Ars. “It’s in an entirely different place.”

“We repeated this experiment six times, under numerous scenarios,” Jadali wrote in a detailed report. “Each time we obtained the same result. In the past, similar [delaying] tactics have been used to avoid data collection” by other browser extensions.

Other tactics

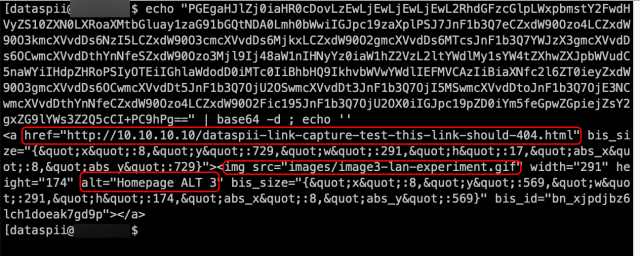

The eight extensions that Jadali identified concealed their collection in other ways. All used base64 encoding and data compression that obfuscated the data being uploaded. The image immediately below shows what data uploaded by Hover Zoom looked like to the naked eye; the second image below shows its contents after being decoded.

These screenshots also show Hover Zoom collecting hyperlinks and image locations of visited pages, even when these are inside a private network. SpeakIt! performed almost identical data collection. As noted in the main article, the collection of hyperlinks and resources is serious because it can give outsiders a birds-eye view of an organization’s private network. Jadali’s research shows this data was being sent to pnldsk.adclarity.com. Adclarity.com is the homepage for AdClarity, maker of a marketing intelligence tool for people in the online advertising industry, which told Ars that it had purchased the data for a trial project but has already stopped using it. There is no evidence of Nacho Analytics publishing or even accessing any of the hyperlink data.

Jadali also observed both Hover Zoom and SpeakIt! sending other browsing data to p.ymnx.co. It remains unclear what this subdomain is or what happened to the data it received.

The data collection was also hard to detect because it continually morphed over the seven months that Jadali tracked it. Some of the extensions, for instance, regularly tweaked the encoding and compression used before uploading user data.

The data collection was hard to track for other reasons. Four of the extensions uploaded visited URLs and page titles in batches ranging from 10 to 50, and the batch size changed regularly over the seven-month span of Jadali’s research. What’s more, websites for three of the extensions used a robots.txt file to prevent search engines from indexing their terms of service and privacy policies.

Watching the watchers

Jadali used browsers with all of the suspect extensions installed to visit a total of more than two-dozen unique URLs on a domain that he hosted. For tracking purposes, the unique URLs he visited contained long strings that specified the time of the visit and the operating system, browser, and extension being used. One such URL was this:

[REDACTED-DOMAIN]/samtesting.html?&os=mac&brow=crmium&v=74.0.3684.0&ext=SZ&date=mar112019&time=149pmpst&socsec

=123004567&customerssn=123004567&lastname=doe&first=john&last=doe&password=

mypass&p=anotherpass&apikey=XYZ

Except for the visit by his lab browser using one of the extensions, Jadali was careful to keep the two dozen unique URLs private. Within about an hour of each visit, however, Nacho Analytics published each link. Because Jadali controlled the domain that was hosting each of the URLs, he was able to track any follow-on visits the links received. Within three hours of being published on Nacho Analytics, a third-party IP address also visited each one of the URLs.

Jadali’s logs show the above link receiving the following Web request:

184.72.115.35 - - [12/Mar/2019:01:03:45 +0000] "GET /samtesting.html?&os=mac&brow=crmium&v=74.0.3684.0&ext=SZ&date=mar112019&time=149pmpst

&socsec=123004567&customerssn=123004567&lastname=doe&first=john&last=doe&

password=mypass&p=anotherpass&apikey=XYZ HTTP/1.1" 200 198 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_10_1) AppleWebKit/600.1.25 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/8.0 Safari/600.1.25"

Who was behind this further collection? Jadali said that one of the five following IP addresses visited each of his test URLs:

- 54.209.60.63

- 54.175.74.27

- 54.86.66.252

- 52.71.155.178

- 184.72.115.35

Not only did the IP addresses visit the URLs for Jadali’s domain, in many cases they also actively downloaded an SQL database hosted by the pages. The download happened on pages hosting databases with sizes of 1.6KB, 9KB, 425KB, and 4.2MB. An 8.4MB database, however, wasn’t downloaded, leading Jadali to speculate that it passed an unknown size threshold designated by the person or script controlling the page visits.

Jadali used both forward and reverse DNS records to trace all five of the IP addresses to kontera.com. The URL http://kontera.com/ redirects browsers to the website of Amobee. A division of Singaporean telecommunications company Singtel, Amobee is an advertising company that bought analytics company Kontera in 2014 for a reported $150 million.

Amobee representatives didn’t respond to messages asking how they obtained the links Jadali observed the Kontera IP addresses visiting or what the company did with the downloaded SQL files.

Jadali said that if these IP addresses visited obscure URLs he had created only a few hours earlier, it’s a reasonable bet they visited many, many others.

“It’s possible they could be analyzing those pages for advertising or marketing purposes,” he told Ars. “Perhaps they use the page content data to deliver advertisements related to the content. However, as DataSpii shows, how do we really know what companies do with our data?”