It’s not just land-based vehicle manufacturers trying to clean up their emissions with electric transport, water-based modes of travel are too.

Take Ellen, the electric-powered ferry that sails the west Baltic sea, for example. Unlike Sony’s recent shock concept car announcement, Ellen is in action and was ready to welcome its first customer aboard late last year.

*chirp chirp*

Who’s there? It’s early bird tickets to TNW2020

Before I tell you more about Ellen, let’s get the important numbers out the way.

According to figures in a recent BBC report and Ship-Technology.com, Ellen will help cut 2,000 tons of CO2, 41,500kg of NOx, and 1,350kg of SO2 every year.

Conventional combustion engine ferries use marine diesel, which is about as close to crude oil as fuels come. However, the only oils on Ellen are in the gearbox and the kitchen, Halfdan Abrahamsen from Ærø EnergyLab told the BBC.

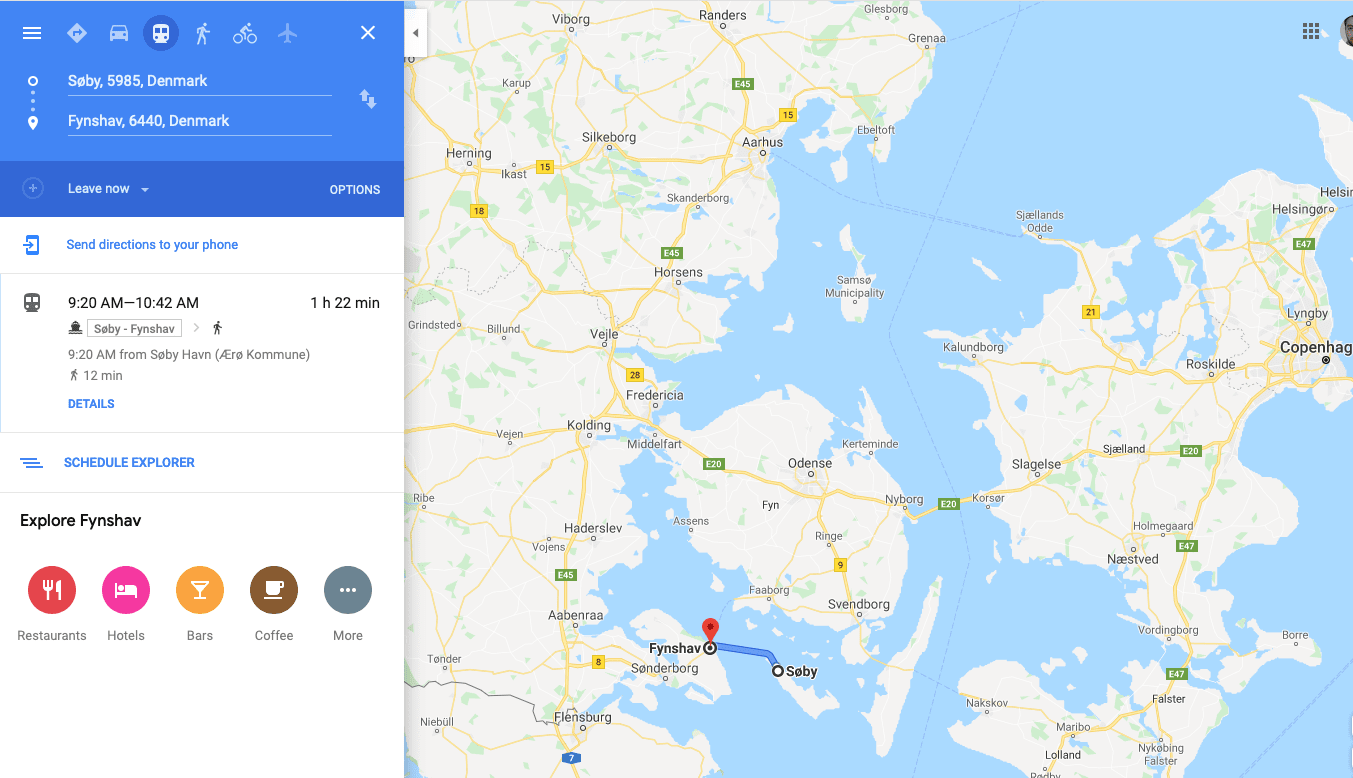

Operated by the Municipality of Aeroe, the all electric ferry sails between the Danish island of Ærø, and Fynshav on mainland Denmark, about a 20km journey.

That’s a hull of a lot of batteries

Like the Musk’s range of Tesla EVs, Ellen is powered by laptop-like lithium-ion batteries, 840 of them, weighing some 50 tons.

The power packs have a combined power output of 4.3MWh (or 4,300kWh). To put that in some kind of perspective, the Tesla Model 3 battery has a peak capacity of about 75kWh. In other words, Ellen’s batteries can hold more than 57 times the electricity of a Tesla.

[Read: Tesla nosedives in Norwegian consumer satisfaction rankings — but drivers stay loyal]

In some ways, that doesn’t sound like much; it’s quite easy to imagine 57 Teslas. But it should be noted that Ellen only has a range of about 22 nautical miles or 38 km before needing to be charged again.

While that’s plenty of range for the 20 km trip, to increase Ellen’s range isn’t as simple as putting loads more batteries on board.

Given its commercial use, and with no option for a backup generator, engineers needed to design the ferry‘s batteries with a level of redundancy.

As project coordinator Trine Heinemann told Ship-Technology.com, Ellen’s batteries were designed in modules and are wired up in such a way that if one batch of modules fails the remaining modules will continue to work and power the ship.

But obviously, as with any electric vehicle, it needs to be charged. But Ellen’s operators have accounted for that too.

Because the ferry has a fairly consistent schedule and journey, it’s quite easy to plan when it needs charging and how much power it will need to complete a days work.

In Ellen’s case, the ship starts a morning with a full battery, and will be put on charge every time it returns to its home port to keep the batteries topped up. A special charging connection awaits in port so no time is wasted before plugging in. This happens about six times in a day.

When the ferry is back at its home port its left overnight to charge back up to 100 percent, ready for action the following day.

It’s not all smooth sailing

According to the BBC‘s report, despite taking its maiden voyage last year, Ellen hasn’t all been plain sailing.

Some battery modules have already needed replacing. But the long term prospects are looking good.

Heinemann told the BBC that running Ellen costs about 25 percent of what an equivalent diesel vessel would cost. While electricity is generally cheaper than fuel, Ellen’s maintenance costs are also substantially lower, too.

The typical marine diesel engine has 30,000 moving parts, just watch this documentary on how they’re made to see just how intricate they are. Electric motors have far fewer moving parts, so there’s a much lower maintenance overhead.

However, given the newness of the technology, there are substantial upfront costs.

The ferry was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 program, which fronted €15 million of the vessel’s €21 million cost to build.

According to Heinemann, Ellen expects to break even in about four to five years. Not bad for what is effectively a prototype and a bit of a world first.

Indeed, it’s going to be awhile until we see electrically powered ferries making long crossings, like the overnight trips from continental Europe to Britain. Fully electric cruise liners and cargo ships will be even further into the future.

But Ellen proves what can be done today, and that’s an important step in the right direction.

Read next: Freelancers can solve the corporate innovation conundrum