Welcome to Riding Nerdy, TNW’s fortnightly dive into bicycle-based tech, where we go into too much detail and geek out on all things related to pedal-powered gadgets.

Cycling is dangerous. In Britain more than 100 cyclists are killed and more than 3,000 are seriously injured each year. Reducing these numbers is no small task.

Let’s go bowling

Join us on Dec. 11 for the ultimate team outing

But one plucky startup from Britain, backed by ex-pro and Australian national road cycling champion Simon Gerrans, thinks it can make cycling safer with its 3D-printed fully-custom bicycle helmet.

Earlier this year, I got to see how the company — called HEXR — was manufacturing its first production run ready for shipping. I even got hands-on with the product, and toured the production facility to see how HEXR is using 3D printing to bring its product to life.

Tackling helmets head on

Whether or not wearing a helmet makes cycling safer is a hotly debated and divisive topic. But logic suggests, should you fall off your bike and hit your head on something – like the road – it’s probably best to be wearing one.

Choosing which helmet is just as divisive. If you’re not a “bikie,” you might not know there’s arms race in the cycling industry to produce the world’s “safest” bike helmet.

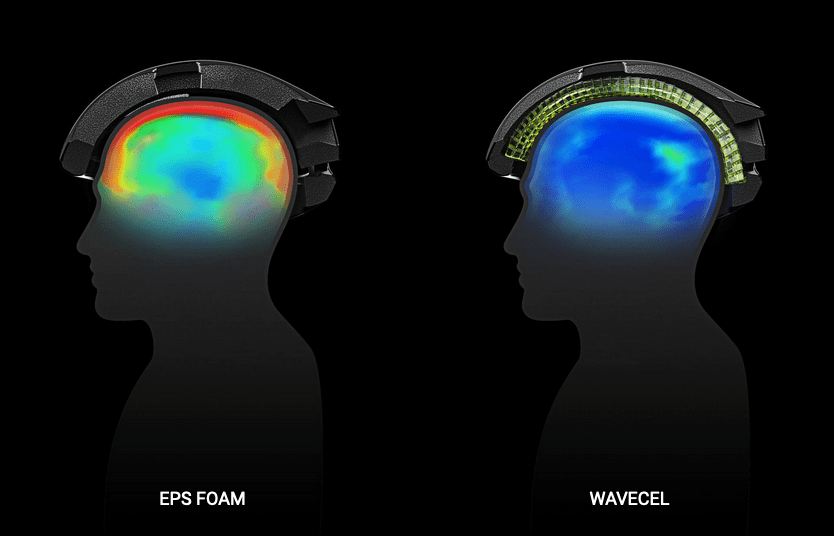

American cycling equipment manufacturer Bontrager recently launched its WaveCel line of helmets, which it claimed greatly reduced peak impact and rotational forces typically experienced in bike accidents. The firm said its WaveCel helmets were 48 times more effective at preventing concussions than traditional foam-based lids.

Not everyone agrees, though.

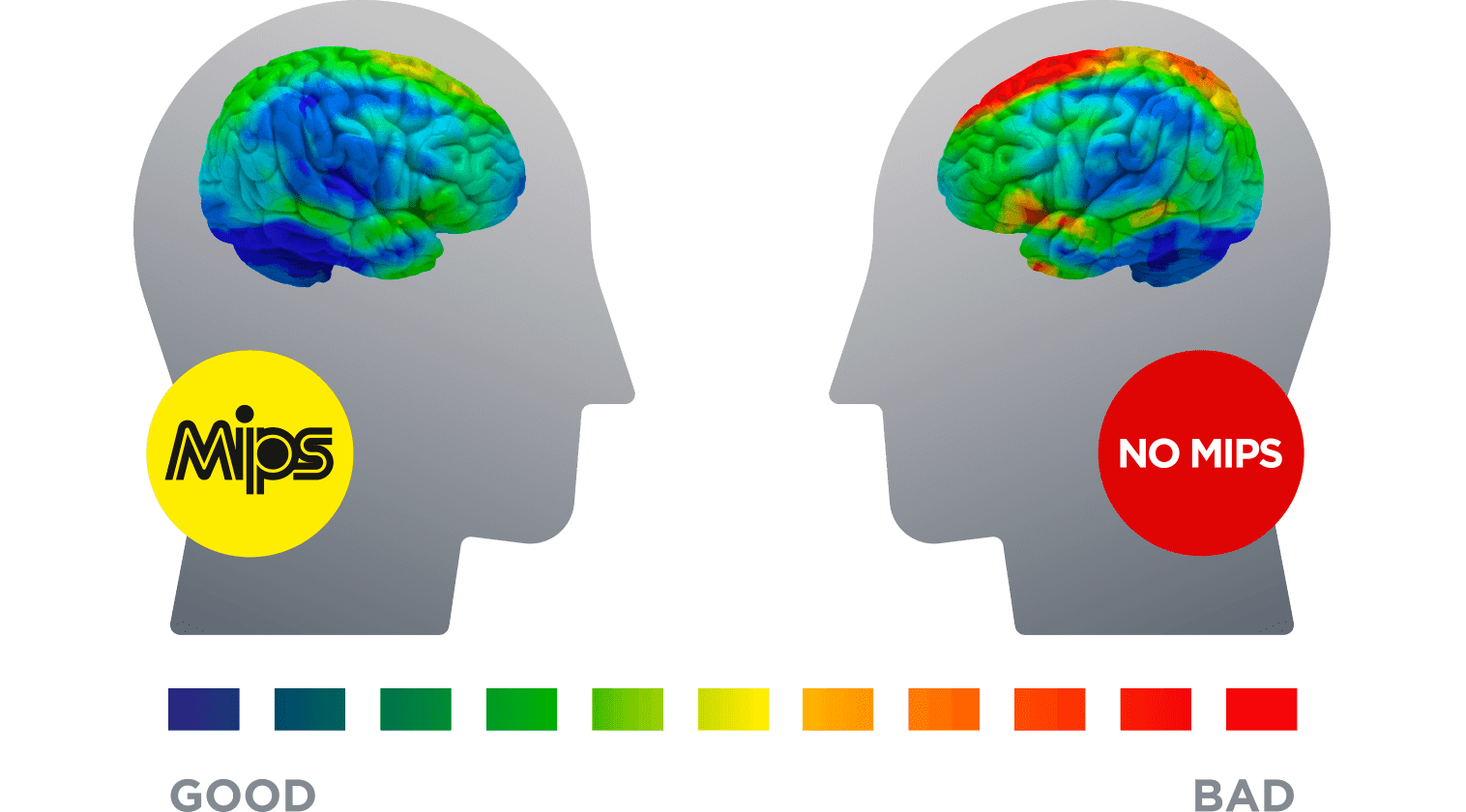

The group of scientists that developed a competing technology, known as Multi Impact Protection System (MIPS), dispute the claims. MIPS engineers found Bontrager’s WaveCel, which is used in a range of bike, ski, and motorbike helmets, to perform “far below the published claims.”

While those firms fight it out, HEXR — the brainchild of ex-Cambridge rower and materials scientist Jamie Cook — has entered the ring. And initial tests suggest its 3D-printed bike helmet will be a force to be reckoned with.

MIPS and WaveCel are effectively “liners” that create a protective interface between foam outershell and the wearer’s skull. They’re designed to absorb rotational forces and oblique impacts better than conventional un-lined helmets. While these are a step in the right direction, HEXR still believes the industry is missing the point and coming at the safety problem from the wrong angle.

The company says that expanded polystyrene or EPS foam, (the stuff that’s usually protecting your flatpack furniture) is far from the best material to make a helmet with, but it’s still the most commonly used.

Foam absorbs impacts best when forces are head-on, against flat surfaces. In reality, bike crashes involve twists, slides, and rotational impacts from various directions, and your head, in case you hadn’t noticed, isn’t flat.

What’s more, EPS foam is terrible for the environment. It doesn’t biodegrade, is made using crude oil, and is wasteful to produce. “It’s 2019, we can do better with our manufacturing processes,” Cook told me as we toured HEXR’s production facility.

By leveraging 3D printing, HEXR thinks it can make a better product both for riders and the environment.

Development, design, and material

HEXR was born during Cook’s university research that explored the effectiveness of different structures and materials for absorbing impacts around spherical objects. His research began in 2013 at University College London, and in 2015, continued as part of a master’s at Oxford University.

“Innovation is always messy,” Cook told me.

Generally dismayed with the current state of the bike helmet industry, Cook decided to take action and find a way to make a better helmet.

“[For] all of these foam helmets, production hasn’t changed in years. If you go into a retail store they’re all pegged up and no one really knows if one’s safer, or fits better. It’s kind of complicated,” Cook added.

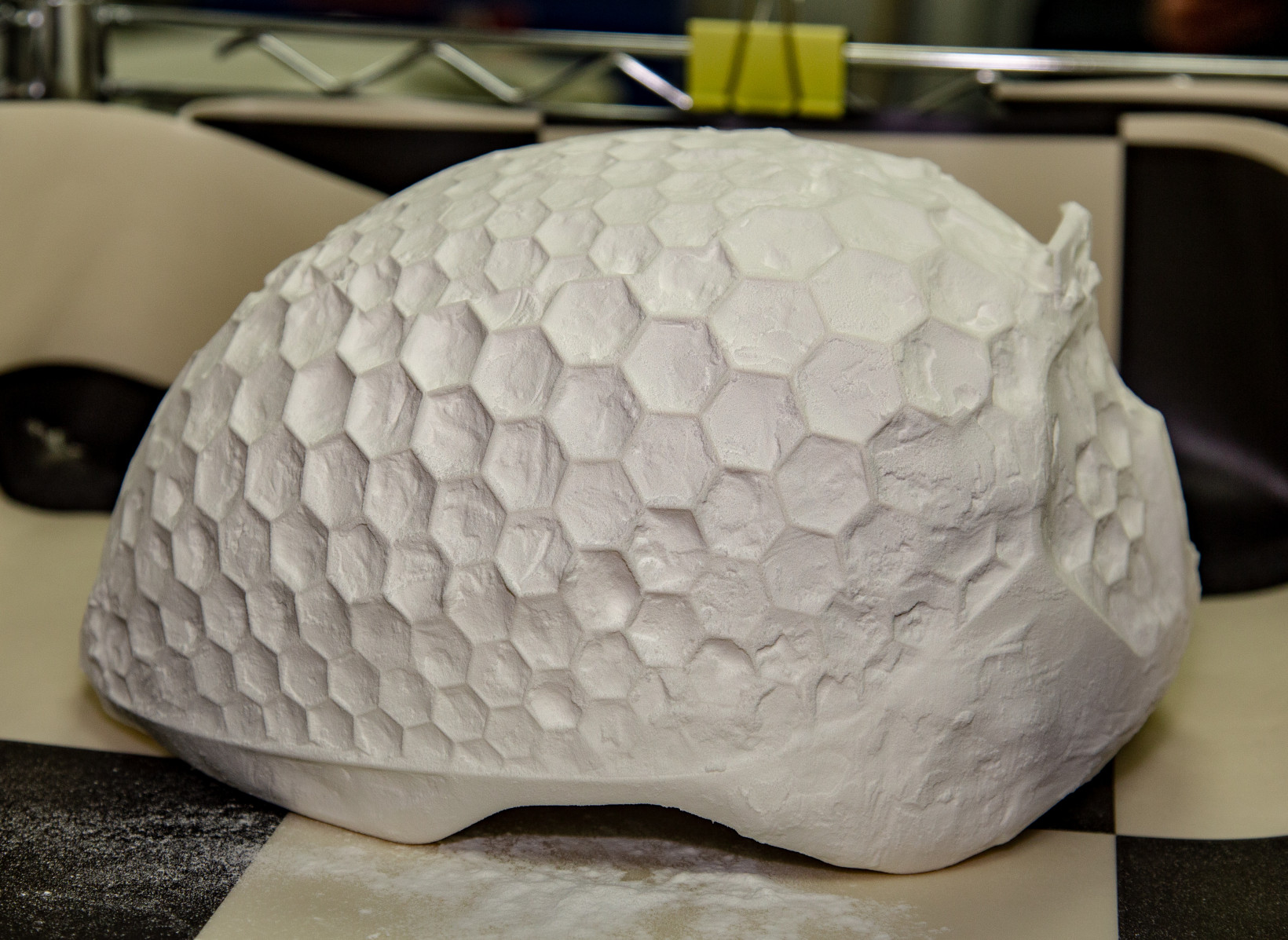

After five years of research, Cook discovered that hexagonal cells performed far better under impact load than EPS foam when surrounding spherical objects, like your head.

Under high impact, foam hardens to the point it stops an impact and transmits forces through the material, which isn’t exactly desireable for a helmet.

Hexagonal cells, on the other hand, buckle, bend, and distort to decelerate a payload against impact, reducing peak impact forces.

Think of it like a load of small crumple zones, like you’d get on a car, but for your head.

“[This helmet] is based on a whole new set of fundamental science around head shape… it’s the first designed around energy absorbing structures,” Cook added.

As a HEXR helmet experiences an impact, the contact area increases across more “cells.” As more cells are recruited, impact forces are reduced and energy is dissipated across a greater area. In reality, this means forces are reduced, rather than transferred through the medium — as EPS foam does — from the point of impact.

Hexagonal cells perform great in the lab, but the biggest challenge Cook says is manufacturing them and scaling production to be sustainable. Producing the intricate hexagonal structures fast and cost-effectively is not easy.

Conventional plastic injection molding techniques are up to the job Cook said, but the issue here is tooling. Injection molding requires a parent mold in which liquid plastic is forced to form the shape of the product.

Manufacturing a mold for the complex, intricate, and thin walls of HEXR’s hexagonal cells would not come cheap or quick. You’d also have to outsource production to the far east, which comes with its own cultural, logistical, and quality control challenges. Again, not something that can happen overnight.

In the case of helmets, manufacturers also need to cater for a range of sizes to fit varying head shapes, which would require more research, time, tooling, and testing to produce a workable product.

Large companies like Under Armour, Adidas, and Asics often work with specialist clothing development firms – like Alvanon – to develop the most appropriate fit for specific garments. As a small startup, HEXR is taking a different approach; because it has 3D printing at its disposal.

Making the helmet

Around the time Cook began developing the HEXR helmet, there was “huge hype surrounding 3D printing,” he said.

“When I first started I was in awe of the technology. But 3D printing is kind of an umbrella term, there are lots of other techniques that fall under this blanket.”

Throughout HEXRs development, the company tested various materials, manufacturing techniques, cell sizes, and layouts, but it was always based around 3D printing. It was continual prototyping that allowed it to test the limits of the hexagonal cell. It simply wouldn’t have been economically feasible with conventional manufacturing techniques.

It’s actually quite heavy-handed to refer to what HEXR does as 3D printing. Its correct term is additive manufacturing, and this is what has allowed HEXR to have an idea, make it, and test it in the real world within 24 hours. In the industry this is referred to as “rapid prototyping,” and it’s one of the technique’s biggest boons to fledgling manufacturers.

It means businesses can try out new ideas quickly, perfect the ones that work, and dismiss the ones that don’t. In the world of bike helmets, that have to undergo rigorous safety testing, it lets manufacturers quickly find and hone the best design.

Interestingly, many firms favor 3D printing for product development for this very reason, but will often steer back to traditional mass-manufacturing techniques when it comes to undertaking the production run.

“Everything was 3D printed, from the beginning,” Cook said. In the early days HEXR was set on embracing this new technology, but it didn’t come cheap. Early prototypes of the helmet cost nearly £1,000 to make.

Given this is a new process, HEXR had to figure out how to do everything from the ground up. Not only did it have to design the helmet, it had to work with manufacturers to find the best way to produce it — to “print” it.

The two most crucial parts were finding the best type of 3D printing and base material to use.

Eventually HEXR settled on a form of additive manufacturing which involves using heat, lasers, and polymer powder to sinter together and effectively “print” the helmet. Turning a mass of powder into a single structure.

After hundreds of prototypes, and thousands of tests (over 3,200 in fact) HEXR found that a solid bioplastic polymer, called Polyamide 11, handles crash forces best and is easy to use in additive manufacturing.

But how do you go from a bucket of Polyamide 11, a fine powder in its raw state, to a solid helmet fit to keep your head safe? That’s where additive manufacturing comes in.

The 3D printing machines HEXR uses are a far cry from the household 3D printers you may have seen already. Each machine is about the size of a big American-style fridge-freezer.

Essentially the helmets are produced through a process of sintering a plastic powder into a series of very specifically shaped layers that are built up over the course of about 24 hours.

Inside each machine sits a metal bucket, about two feet tall, by one foot square. The metal buckets are home to a platform on to which the helmets are “printed.”

The platform in the bucket mates up to a hopper or “head” inside the machine that moves across it every few seconds, depositing a one micron layer of the Polyamide-11 powder each time. It’s similar to the way a printer head moves across a piece of paper.

After every cycle of the head, lasers draw what is effectively a two-dimensional shape on the powder. In reality, this shape is one of the 3,000-plus layers of material that will go on to make the helmet. These lasers are infact sintering and melting the powder together into a very specific shape.

As the platform moves down, more powder is added, and the lasers continue to sketch out the helmet’s layers based on a computer-aided design generated by HEXR.

The environment inside the machines is intentionally kept at a temperature just a few degrees below the melting point of the polymer powder, about 175C. This is so the lasers sketching out the shape of each layer, can push the powder beyind its melting point. When this happens, the powder melts together, cools, and forms a solid.

However, lots of powder doesn’t actually go on to form part of the final product. It sits in the printing bucket having not been sintered; but it still plays an important role in the helmet’s construction.

As the helmet is being printed, the redundant powder supports the helmet’s shape until it’s sufficiently cooled and hardened.

Thanfully this extra powder isn’t wasted, though, as it’s recycled and resused. Unlike traditional manufacturing processes, 3D printing doesn’t generate much waste material.

“There could be powder used here that’s been in circulation in our printers for many years,” Frederick Wray from 3T Additive Manufacturing (HEXR’s production facility) told me as I watched the sintering process.

The material does degrade slightly over time, eventually forming small lumps, but these are continually sifted out so only the good polyamide is put back into circulation, Wray added.

What’s more, Polyamide 11 is

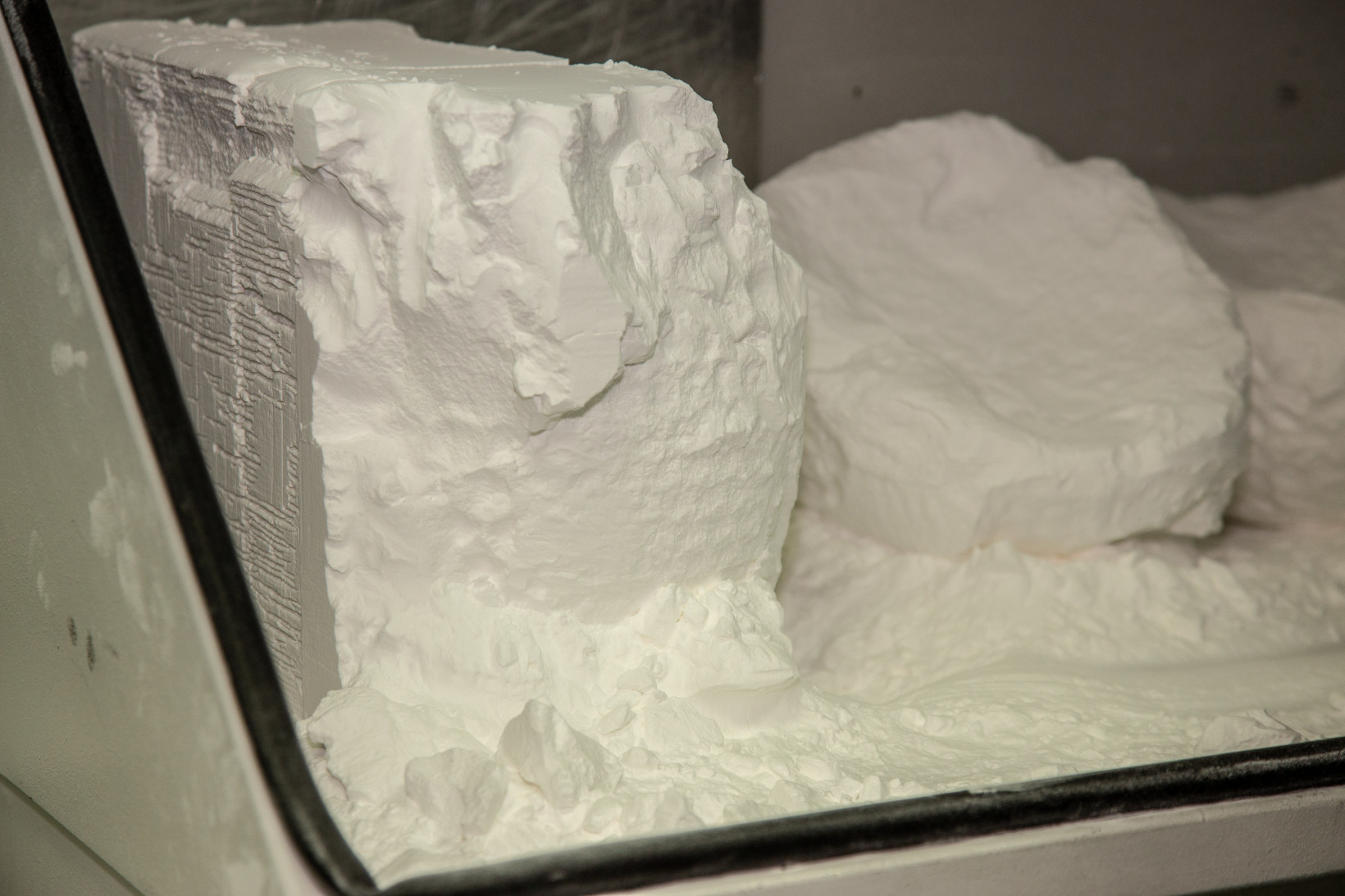

The breakout

Perhaps, the most interesting and exciting part of the production process, as a spectator at least, is what Wray refers to as “the breakout.” This is when the blocks of powder, and printed helmets, are removed from their metal buckets. Hard product is separated, in an archaeological dig-like fashion, from the loose un-sintered powder.

It’s also the first part of the process which requires human intervention.

Once the excess powder is removed from the printed helmets, they are cleaned, primed, painted, and finished. This final part of production involves adding soft fabric pads inside the helmet, straps, and a clip on vacuum formed aerodynamic plastic shell.

As it happens, most of these other components are made or assembled in the UK too — not far from where the helmets are printed — further keeping the overall carbon footprint of the product down. The helmet’s “aerodynamic-shell” is made and painted in Fareham, UK. Chin straps are assembled in the UK, as are the helmet’s ratchet and buckles.

All these elements can be replaced individually too, so if a buckle or a strap breaks, HEXR can send you replacements, further reducing unnecessary waste.

HEXR can produce about six helmets in one machine, the company’s UK facility has about eight machines running around the clock.

But it should be noted, unlike mainstream brands, which will have production runs of hundreds, if not thousands of units at a time, HEXR makes only what needs to be made. Just one custom helmet for each individual customer.

Without 3D printing, HEXR would have taken many more years to reach the market. It probably would have come at a far greater environmental cost too. But the benefits of additive manufacturing don’t stop here.

One of the biggest challenges with making helmets – or any clothing for that matter – is sizing. Typically manufacturers will develop a selection of different sized helmets that fit a range of head sizes with ratchets and tightening mechanisms to provide some tolerance for different headshapes.

HEXR takes advantage of the firm’s 3D printing manufacturing process to make every single helmet specifically for each customer’s head shape.

Going fully custom

Before getting a HEXR helmet, every customer must don a swimming cap type hat and have their head scanned. Interestingly, the technology used to contact the scan is fairly run of the mill; it’s an iPad and some depth sensing cameras. These cameras are becoming increasingly common in mainstream smartphones. HEXR expects to be able to let customers scan their own heads with their own phones soon.

“Most modern smartphones have the capacity to complete a head scan to the standard we need,” Cook tells me as he circles my head, scanning it as he goes.

Alongside its additive manufacturing process, the headscan is a crucial component to HEXR’s manufacturing process, Cook says. It collects 30,000 data points which are used to reconstruct a digital model of the customer’s head which is then used to compute a personalized CAD blueprint for a helmet.

HEXR holds on to these measurements so it can reprint more helmets if you want to buy another or replace one in the case of a crash.

Another function of the head scan program that builds this digital model is to find the most efficient way of printing as many helmets as possible in one AM machine at a time. The program takes all available orders due to be printed, and finds the most efficient way of positioning them in the machine to print as many, in as little time as possible.

Safety first

I have to ask, is HEXR’s radical approach to manufacture and design worth it? In other words, is HEXR’s use of 3D printing actually making a safer helmet? Custom is one thing, but it’s got to perform. After all, a helmet’s primary function is to protect your head. So does it?

The short answer? Yes.

Initial third-party tests show HEXR’s designs are beating out the competition, and are doing it with aplomb. And these aren’t self-made tests designed to make the helmet look better, these are industry standard tests, conducted by the British Safety Institute (BSI) that all helmets sold in the UK must go through.

HEXR’s 3D printed helmet doesn’t just satisfy the minimum (EN 1078) requirements of these tests, it far surpasses them.

The BSI tests helmets by dropping them (with a fake head inside) on to an anvil; linear impact forces are recorded by sensors inside. Under EN 1078 standards, helmets are required to deliver a peak deceleration force of less than 250G. HEXR’s helmets produced an average linear force of 144G.

There is no industry testing for oblique non-linear crashes at the moment — even though they represent a huge risk to crash victims. Professor Remy Willinger at the University of Strasbourg developed the testing protocol that’s used by MIPS to simulate the twists and rotations often experienced in real life accidents and applied the methodology to HEXR.

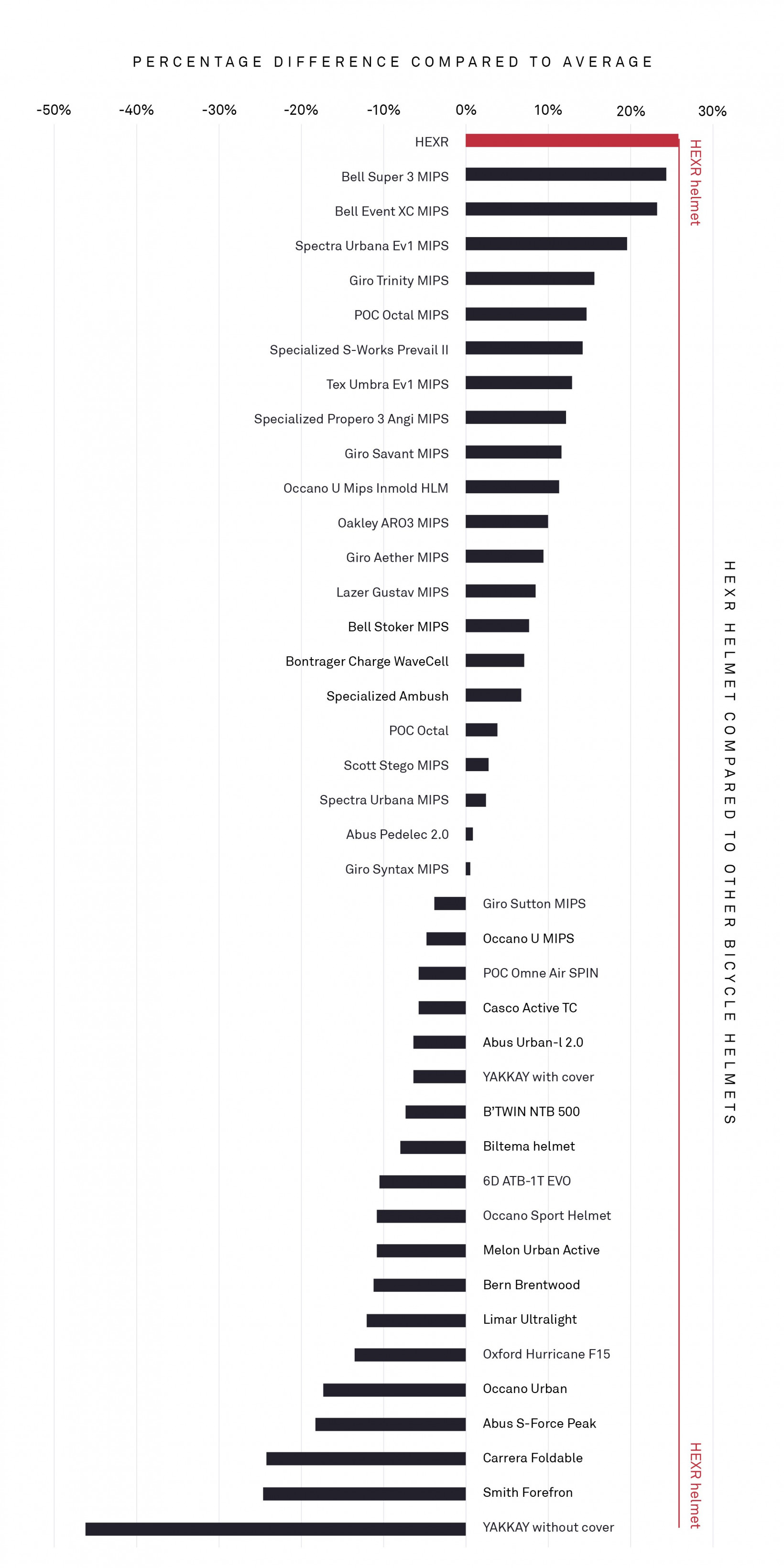

Prof. Willinger found that in two of the three oblique tests, the 3D printed lid out-performed 32 other helmets from a rangemarket leading brands.

However, in the one remaining test, HEXR performed just ok, not the worst, but far from the best. So there is still work to be done. That said, the test result indicates the risk of injury from this particular impact is still less than 30 percent, most other helmets tested fall around the 25-percent mark, so HEXR isn’t far from the average.

Another independent test, conducted by Swedish insurance firm Folksam, using the same testing methodology as Willinger, found the HEXR helmet to be the safest helmet on average compared to 40 others from market leading brands – including over 15 that use MIPS technology and one that uses Bontrager’s WaveCel liner.

It all sounds great doesn’t it? And I would for the most part agree, but there are some caveats.

The low down

The pros are obvious. HEXR’s made from eco-friendly sources, it’s less wasteful, and as initial testing shows, it’s safer than most other conventional foam helmets. It’s also lighter, and claims to be more aerodynamic two important characteristics for keen cyclists.

And in my personal opinion, having spent an afternoon with one, it looks incredible. It’s like no other helmet on the market today, if turning heads is your thing, it might be right up your street.

But there is a catch. Its price.

It’s £299 ($390).

That’s a lot of money for a helmet, even for hardcore cyclists. Comparing similarly priced road helmets, the only ones that come close are specialist aerodynamic time trial helmets that have had thousands of hours worth of wind tunnel R&D poured into them – such as the Giro Aerohead Ultimate with MIPS.

Interestingly though, if you’re comparing HEXR to other helmets purely on its safety ratings it’s worth noting that a 2018 study by Virginia Tech found that price doesn’t correlate to safety. Just because you spend more, doesn’t mean you’re getting a safer helmet. But then again, so far HEXR has largely outperformed and is unlike the competition, so it’s an outlier to the trend.

HEXR claims its helmet is one of the lightest on the market too, and those don’t come cheap either. Typically, high-end road helmets weigh around 200g, like the Specialized S-works Prevail that costs $200. It’s hard to pin down exactly how much a HEXR weighs as everyone gets a different size, but the ones I’ve seen were around 230-250 grams.

People spend a lot of money on bicycles too, in the grand scheme of what an individual might spend on cycling kit, a HEXR helmet might represent less than 10 percent of the outfit’s total cost.

This isn’t an attempt to justify HEXR’s hefty price tag, rather it highlights that expensive helmets exist and people do buy them. HEXR’s helmet is not a mainstream product, it’s targeted at a very specific audience, for now. Personally, I’m excited about what will happen when this technology breaks into the mainstream at lower price points.

Perhaps the biggest factor that will set HEXR apart from the crowd is comfort. Early users and pre-production reviewers are saying it’s the most comfortable helmet they’ve ever worn. That’s quite a bold claim, one I will be testing for myself as I get to try out a HEXR helmet made for my own head.

Now, I’m yet to use one but would I buy one for myself at this price? At the moment, probably not, it’s going to have to deliver Rolls-Royce levels of comfort for me to change my mind about that. I would, though, recommend HEXR to those that can afford it, and hopefully some day it’ll come down to a price that makes it accessible to a much wider audience.

HEXR’s environmentally conscious approach to manufacturing is an undeniably good thing. But until one needs another helmet, it would just be additional superfluous consumption to buy one.

Catching up with expectations

Ten years ago, the words 3D printing were splattered across the headlines. It was largely hailed as a new technological panacea that would disrupt traditional manufacturing, allegedly for the better. In December 2010, PC World magazine ran a feature titled: “The 3D printer revolution countdown.” Earlier in the same year, New York Times ran a piece titled “3D printing spurs a manufacturing revolution.” Business Insider called it the “next trillion dollar industry.”

But it seems we’re still waiting. According to market research firm Smithers Pira, the 3D printing industry will be worth $55.8 billion by 2027, we still have a long way to go before it’s a “trillion dollar industry.” Headlines of today, are more sedate.

3D printing is happening, you can buy small items, phone cases, whistles, and general small plastic things. In most other cases, 3D printing is largely used as part of the product development process, where firms take advantage of its “rapid prototyping” capabilities.

Large scale manufacturing is only just starting to engage with the technique, and interestingly, the cycling industry is taking a lot of notice. Recently, one of the world’s biggest bike manufacturers Specialized announced a 3D printed version of a racing saddle. And Silicon Valley composites company Arevo displayed its 3D printed bike frame at Eurobike earlier this year. But both these products are a way off yet.

If you’re not into bikes or cycling you probably won’t care a whole bunch about HEXR or its helmet, I understand, it’s a niche product.

But you should care about what the company is doing with its environmentally conscious additive manufacturing process. It’s one of the most tangible, real-world use cases of the technology. And it’s happening now.

HEXR remains unique, not just in the helmet world but in the manufacturing world.

For more gear, gadget, and hardware news and reviews, follow Plugged on Twitter and Flipboard.

Read next: Iranian gov reportedly offering bounties to those who rat out illegal Bitcoin miners